Built in 1785 as a summer home by Alfred Moore,

Moorefields is more than a house or piece of land, it’s a place of great significance with a rich history.

History

Alfred Moore, born in 1755, served as a captain in the First North Carolina Regiment and later in the coastal militia during the Revolution. A founder of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the nation’s first public university to enroll students, Moore was a leader in early education in the United States. Most notably, he served as an Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall from 1800 to 1804.

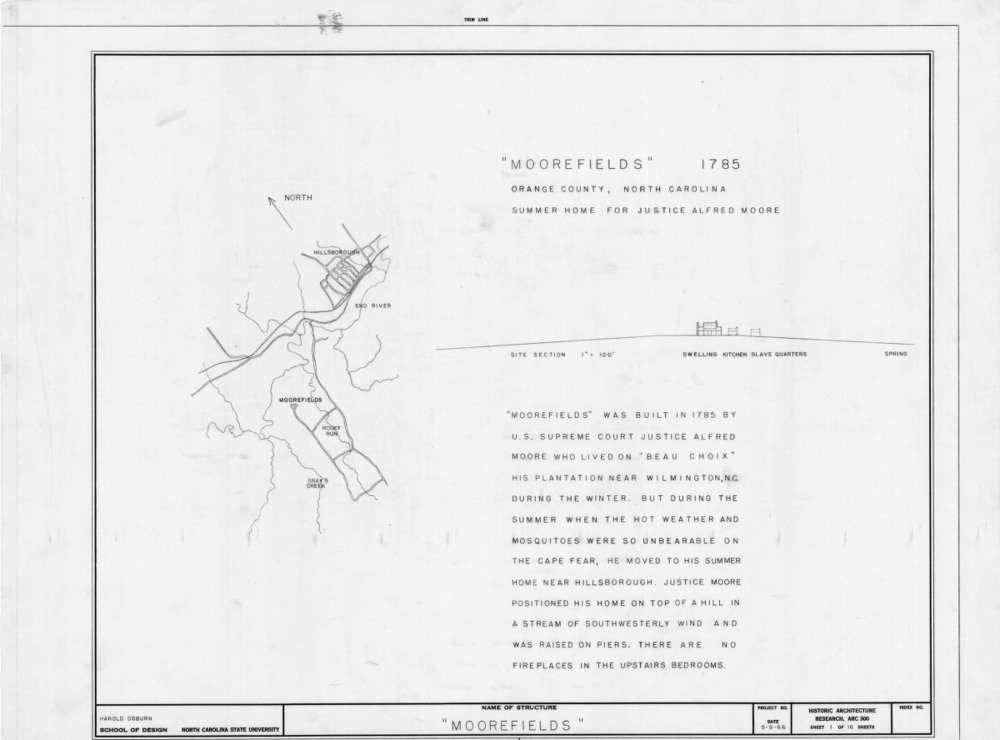

Moorefields was built in 1785. Well before Raleigh was designated as the state capital, Hillsborough, a center of commerce, was the site of North Carolina’s courts and Moore the state attorney general. To reach the Orange County seat in what was then considered the state’s western reaches, Moore traveled a week by wagon from Buchoi, his plantation south of Wilmington along the Cape Fear River. According to legend the Moores fled to the modest Occoneechee Mountains from May until the third hard frost, usually in late October, to escape the heat, mosquitos, and disease of the coast.

The house at Moorefields is located three miles from the courthouse in Hillsborough (five miles by modern road) and strategically situated upon one of the highest points in central Orange County, where in summer it catches the prevailing southwest breeze. Shade was provided by 50 white oaks planted around the house when it was built. The last of the grove fell during Hurricane Fran in September 1996.

The Moorefields site came into European hands when Colonel John Gray, a militia officer, received a 500-acre land grant from Lord Granville on March 25, 1752, half a year before Orange County was formed and two years before Hillsborough was founded.

On September 9 of that year Grayfields, as the plantation was called, was the site of the first session of a Court of Common Pleas and Quarters Sessions held in Orange County. Orange was the most populous county in the west and so large it stretched to the Virginia border and included the present Caswell, Person, Chatham, and Alamance counties as well as parts of Durham, Guilford, Lee, Randolph, Rockingham, and Wake.

The Regulators, protestors against what they considered corrupt, distant government and arbitrary taxation, organized in Hillsborough in 1768. Three years later they fought and lost the battle of Alamance against troops under the command of Governor William Tryon. Alfred Moore served as a lieutenant in Tryon’s service at the battle. Later Moore’s father, Maurice Moore, was a presiding judge at the trial that resulted in the hanging of six Regulators in Hillsborough on June 9, 1771.

The Moores were a prominent coastal family that included several early governors of South Carolina. Their income derived from agriculture and the sale of enslaved Indian and Black people. In 1725 Moores founded Old Brunswick, the first permanent English settlement on the Cape Fear, located 13 miles south of Wilmington. Up the road from the state historic site stands Orton Plantation, built by “King” Roger Moore, whose brother was Alfred Moore’s grandfather. Orton is the last survivor of 66 manor houses built in the area during colonial times, including a plantation named “Moorefields” located north of present-day Wilmington.

Alfred Moore, born on May 21, 1755, read for the law under his father. At age 20 he was appointed a captain in the First North Carolina Regiment under the command of James Moore, his father’s brother, a noted military leader. The Moores fought the Tories at the Battle of Moore’s Creek in February 1776, a major early victory for Colonial troops. Along that day was Col. Francis Nash, Alfred Moore’s brother-in-law. Nash, mortally wounded the following year at the Battle of Germantown, is the man for whom Nashville, capital of Tennessee, is named.

Moore resigned his Continental commission after his father and uncle both died of disease on January 15, 1777. He remained on the coast and continued to disrupt Tory operations as a guerilla colonel. British Major James Craig, later governor of Canada, offered Moore amnesty and restoration of his property upon condition he lay down his arms. Moore refused, and his homeplace was ransacked.

Moore became a state senator from Brunswick County in 1782, a year after Gen. Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown effectively ended hostilities in the Revolutionary War. The N.C. General Assembly named Moore the state’s attorney general in 1783, a position previously held by James Iredell, for whom Iredell County (Statesville) is named. Moore served in the position for nine years.

Junius Davis, in an 1899 speech dedicating Moore’s portrait in the chambers of the North Carolina Supreme Court, described the jurist as “small in stature, scarce five feet four inches in height, neat in dress, graceful in manner, but frail of body.” (Moore is often erroneously identified in histories of the courts as standing four feet, five inches tall.) Davis also ascribed to Moore “a dark, singularly penetrating eye, a clear sonorous voice” and “a keen sense of humor, a brilliant wit, a biting tongue, a masterful logic (that) made him an adversary at the bar to be feared.”

Moore acquired Gray’s property near Hillsborough in 1785, a year after a county was cut from Cumberland and named in his honor. He renamed the site “Moorefields” and over the years amassed 1,202 acres, more or less. Moorefields was a mile and three-quarters at its widest and more than two miles from north to south.

While spending summers in Orange County, Alfred Moore became a founder and benefactor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He served on the board of trustees from 1789, when the university was established, through 1807. Moore was among those who selected the site at which the state of North Carolina established the first public university to open its doors in the United States. He helped prepare a bill for prohibition of distillation or retailing of spiritous liquors within two miles of the school, and served on a committee that chose the device for the seal of the university corporation. While seeking to encourage subscriptions to the university in 1793, Moore was among its largest benefactors, contributing $200 and a pair of globes, the first apparatus for instruction presented to the institution of higher learning.

Meanwhile, in 1792 Moore, a Federalist, returned to legislative office, winning election to the state House of Commons. Two years later, at a time when state legislatures chose U.S. Senators, he was defeated by a single vote in seeking that office. Moore became a Superior Court judge in 1798 and the next year was nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court by President John Adams.

Moore became an Associate Justice, again succeeding Iredell, in August 1800. He retired in February 1804. During Moore’s brief tenure the U.S. Supreme Court decided Marbury v. Madison, the case that established the doctrine of judicial review, asserting the right of American courts to overturn legislation deemed to violate the U.S. Constitution. Moore did not participate in the decision because he was en route to the capital when arguments in the case were heard.

Moore died at age 55 on October 15, 1810 at Belfont, his daughter’s home in Bladen County in eastern North Carolina. His son Alfred Moore, at one time the Speaker of the N.C. House, retained Moorefields and is buried in the family graveyard southwest of the house. So are two of Justice Moore’s daughters, Augusta W. Moore and Sara Louisa Moore.

Moore's descendents included James Iredell Waddell, a Pittsboro native raised at Moorefields and later the commander of the CSS Shenandoah, the last Confederate warship to surrender following the Civil War; and Alfred Moore Waddell, a Confederate cavalry colonel, Congressman (1871-79) and later mayor of Wilmington. Alfred Moore Waddell was a leader during a 1898 white race riot in that city that caused the death of numerous Black residents and took control of Wilmington from its elected officials, the only such insurrection in American history. Both men were descendents of General Hugh Waddell, regarded as the most prominent military leader in colonial North Carolina.

The Moorefields property was divided into five sections in 1847 in accordance with the terms of Justice Moore’s will. The segment containing the house — bordered by Rocky Run to the east, Seven Mile Creek to the northwest, and Gray’s Creek to the west — stayed longest in the family, ultimately purchased in 1913 by Thomas and Louise Webb. Six years later they sold the property to Ada and June Ray.

The Rays sold their 157 acres on May 14, 1949 to Edward Thayer Draper-Savage. The new owner was a noted artist and UNC French instructor who translated for French pilots training at Chapel Hill’s Horace Williams Airport during World War II.

Draper-Savage came upon Moorefields while looking for a place in the country where he might build a cinderblock studio in which to do sculpture and painting. Only after purchasing Moorefields did Draper-Savage, a Wilmington native, discover he was related by marriage to the Moores.

Draper-Savage, who drove a U.S. army ambulance in Europe in World War I, stayed on to live in Paris during the 1920s and early 1930s, Upon acquiring Moorefields he removed most of the farm buildings and laid out formal gardens in the French style. Included are a quarter-mile of privet hedges interspersed with junipers and flower beds. Draper-Savage also extensively restored and preserved the house, and for his efforts in 1960 was awarded the prestigious Cannon Cup by the North Carolina Society for the Preservation of Antiquities, precursor of Preservation North Carolina.

The Historic American Building Survey described Moorefields, one of the North Carolina’s earliest surviving examples of Federal style architecture, as “an elegant small rural manor house” and its uncommon, colonial Chinese Chippendale staircase the “most spectacular feature.” Reflecting the building’s historical and architectural significance, Moorefields was among the first North Carolina homes placed in the National Register of Historic Places in April 1972.

The most notable alteration to the structure — essentially a high central core with flanking right-angle wings divided into two rooms on each side — was the enclosure of the porch connecting the wings on the north side where an old roadway once lay. A canopy was added over the entrance. Draper-Savage also restored the shed roof to the front porch, then removed the front stairs. They were later restored.

The parlor with its 14-foot ceiling was originally used for meals, the smaller rooms in the wings as bedrooms. Each corner post of the parlor, or Great Hall, is comprised of a single tree trunk. Most flooring in the house is the original heart-pine. The moldings, weatherboards, visible mantels and the western chimney are also original. Hand-hewn pegs and hand-wrought, rosehead nails were used in the construction.

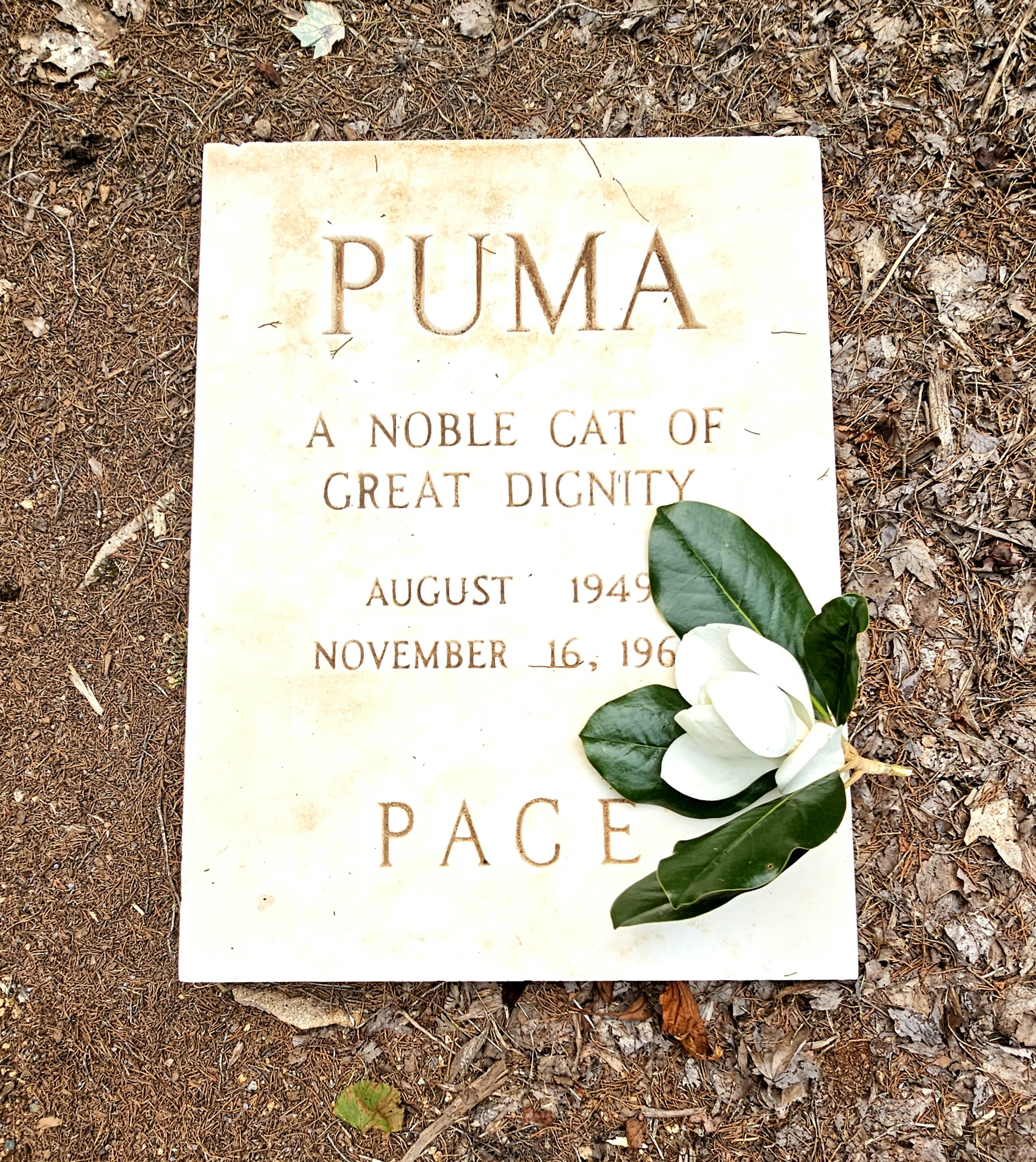

Draper-Savage died in the house on February 15, 1978 and is buried immediately to the west flanked by his cats. Each cat lies in a hand-made, velvet-lined coffin beneath marble markers Draper-Savage designed and executed. Upon his death the house and remaining acreage were conveyed to the Effie Draper Savage-Nellie Draper Dick Foundation for the Preservation of Moorefields. Named after Draper-Savage’s mother and her sister, the foundation was dedicated to maintaining the house and 70 acres of manicured grounds, woodlands and pasture in perpetuity. The property is now owned by the Friends of Moorefields, a 501(c)(3) non-profit which continues to carry out this vision.

All furnishings in the house, including a remarkable collection of 19th century portraits of ancestors from Connecticut and Massachusetts, belonged to Draper-Savage. Among those depicted from life is Sukey Vickery, whose novel “Edith Hamilton,” published in 1803, was among the earliest examples of realistic American fiction written by a woman. She sat for her portrait in 1804.

The house was extensively renovated in 1982, with facilities added on the second story to accommodate a caretaker or renter. More recently the roof, heating and cooling systems, front porch and front stairs, eaves, and electrical wiring were replaced through gifts and grants from individuals, businesses, and corporations, as well as income from special events. The house also was repainted inside and out and asbestos removed from pipes and the boiler beneath the house.

The four acres of lawn, quarter-mile of privet hedges, carefully delineated paths and flowerbeds established by Draper-Savage are tended by organic methods. No pesticides or herbicides are used on the 40 acres of permanent pasture, a quarter of which is devoted to apiary pursuits.

The Cameron-Moore-Waddell Cemetery lies to the southwest of the house, with graves dating to the mid-1800s. A 2023 archaeological investigation funded with a federal and state grant for hurricane relief seeks to learn more about the lives and work of the enslaved inhabitants of Moorefields, and others.

The crepe myrtles just inside the fence and the semicircle of red maples and red oaks on the south lawn were planted in 1982. The entire property, maintained as a wildlife refuge for nearly 75 years, abuts Orange County’s 300-acre Seven Mile Creek Nature Preserve. A conservation easement on the property supported by the NC Land and Water Conservation Fund, Orange County and the Eno River Association will preserve the land in perpetuity. A section of North Carolina’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail also traverses the northern edge of Moorefields.

The Friends host spring hikes led by experts who assist visitors in identifying wildflowers and later birds; conduct monthly open houses on Last Sundays from May through September; and since 2014 have staged an autumn bluegrass festival on the front lawn featuring local artists. Located at 2201 Moorefields Road in Hillsborough, Moorefields is otherwise open by appointment only.